Korean cults, a hotbed of crimes - SCMP

What’s behind South Korea’s attraction to fringe churches?

- The appeal of these ‘cults’ may reveal a grim truth about South Korean society and the way the groups address a search for meaning not found elsewhere

When Ahn So-young was 27, her parents became concerned about her all-consuming commitment to a fringe church group called Shincheonji. They enrolled her in a counselling programme to help her break her attachment to the group. Ahn became so dejected she tried to kill herself by swallowing soap and shampoo.

Anh had been a member of Shincheonji for five years. She spent all her time with the group, even handing out surveys at university to attract potential new members, and eventually quit her studies.

“During my five years inside the group, I feared going home and I interacted less with my parents as I increasingly lied to them,” she says. “My contacts with school friends stopped.”

Her parents intervened and insisted she complete a month-long programme, during which counsellors studied the Bible with her to expose Shincheonji’s outlandish claims, including their insistence its leader, Lee Man-hee, now 90 and in poor health, would live forever as the second coming of Jesus Christ.

Ahn, though, struggled to move on and was overcome with depression. She tried to commit suicide both during the counselling and after she returned home. Shincheonji members even visited Ahn’s house and threatened to sue her parents for coercing her into leaving the group.

“I would try to jump in front of cars to end my misery,” she recalls. “My whole world was turned upside down in just a matter of days, so I was in a world of disbelief and disappointment.”

An honour guard during a funeral service for Reverend Sun Myung Moon, the founder of the Unification Church. Photo: Reuters

A growth industry

There are 14 million Christians in South Korea and Ahn’s story is one of many illustrating the outsize influence such groups – many promoting cultish behaviour and fringe beliefs – manage to wield over some of them. Indeed an estimated 2 million South Koreans are involved with these fringe churches.

Many of them have connections to major corporations, providing them with enough wealth to hold events in World Cup stadiums and build mega-churches with massive auditoriums.

For example, Ilhwa, a major food and pharmaceutical company which makes the popular Mc Col beverage, is affiliated with the Unification Church, which was founded in 1954 by Reverend Sun Myung Moon, who also claimed to be the second coming of Jesus Christ. He died in 2012, aged 92.

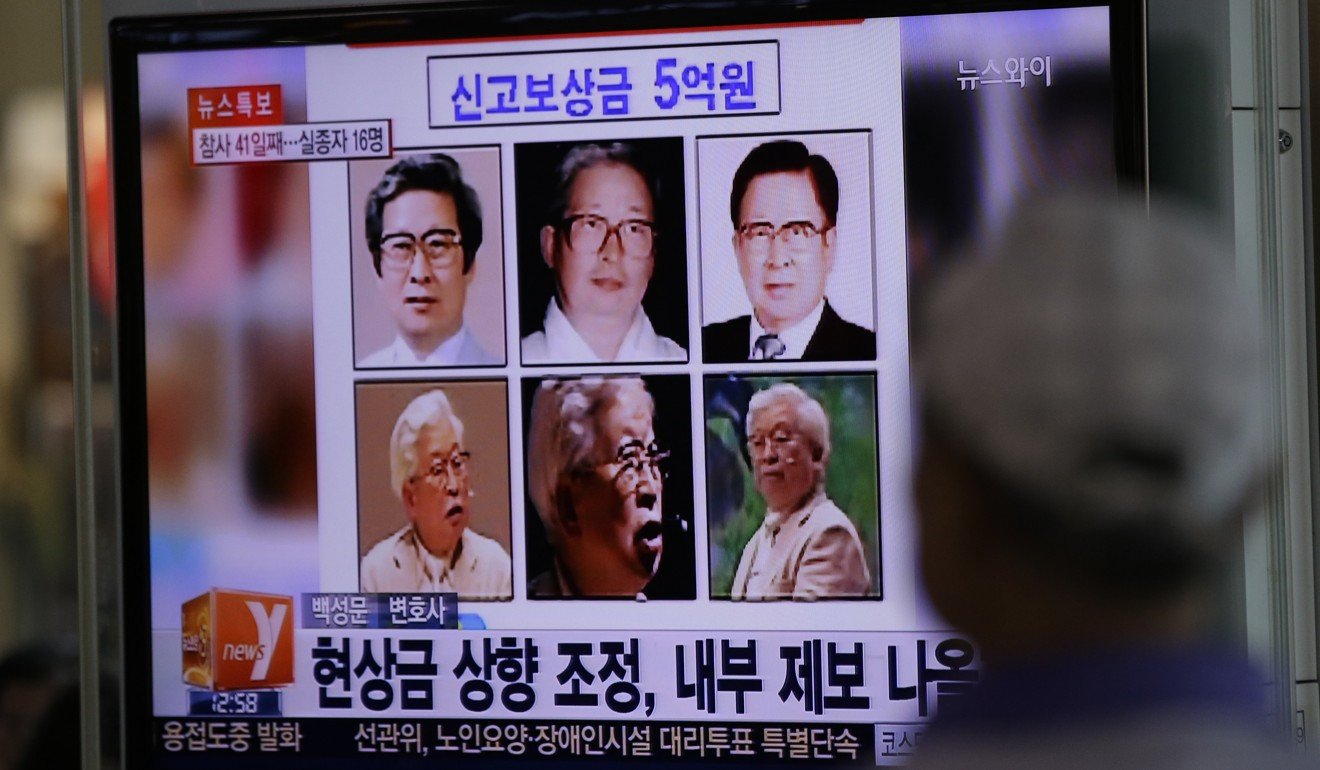

Yoo also founded the Evangelical Baptist Church of Korea – known as the Salvation Sect. The group had previously been investigated over its connection to a mass suicide in 1987 in which 32 members of a splinter group of the church killed themselves.

Yoo was never apprehended over his connection to the Sewol disaster. However, he was found dead in a field after two months on the run.

Shincheonji, which Ahn joined, is the country’s biggest Christian fringe group, with 200,000 members. Its members attend traditional churches to convert members. Consequently, many entrances of churches in South Korea have stickers stating that “Shincheonji members are not allowed inside”.

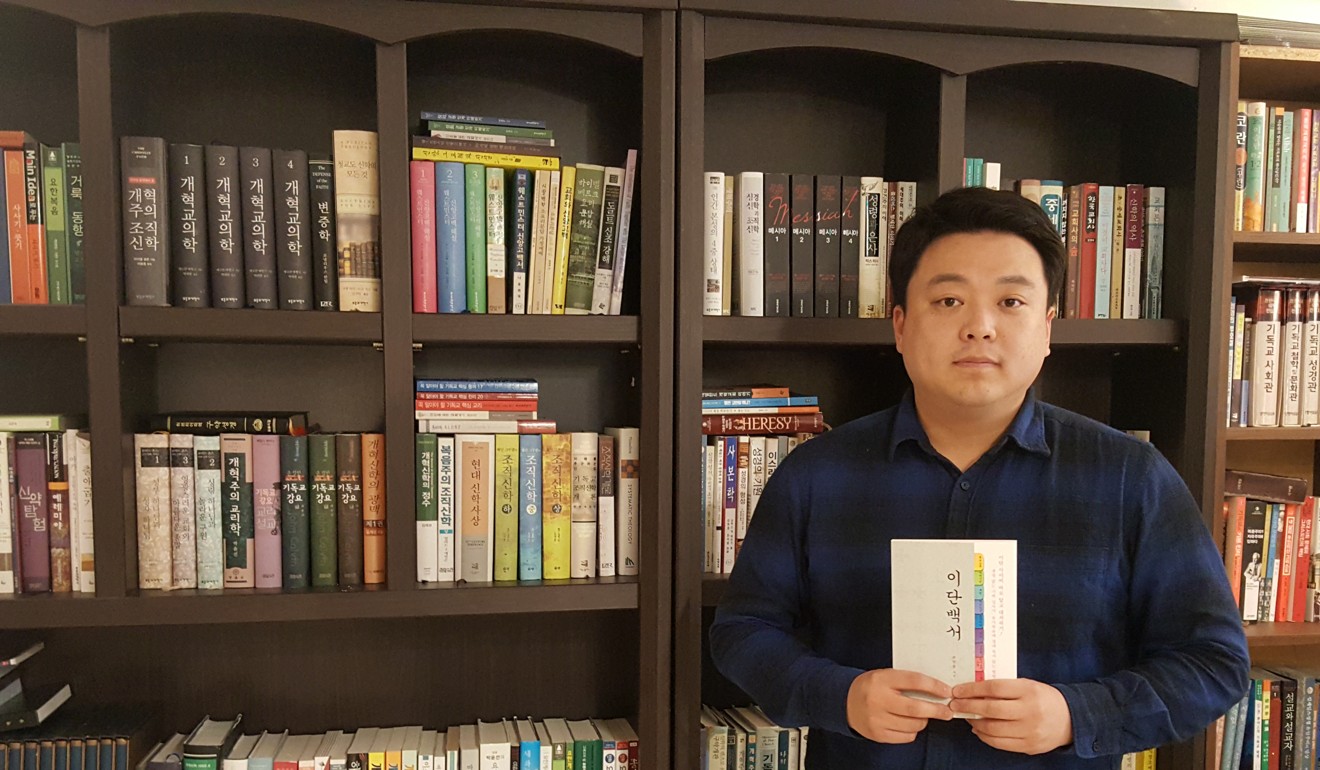

Jo Mit-eum, a 35-year-old pastor, founded a company, Bareunmedia, to help educate people about these groups and the tactics they employ. He insists the government needs to be more aggressive in cracking down on them.

“Shincheonji preaches to divorce from one’s spouse and other groups strongly advise people to quit their studies and jobs,” he says. “The government is not doing much to combat these groups. Since this is considered a religious issue and our country highly values the freedom of religion, pseudo-religious groups are free to do as they wish.”

Easy to get in, hard to get out

Kim Sun-gyo – an alias – was in high school when she first came into contact with members of JMS (Jesus Morning Star) – although the letters actually stand for the initials of its leader, Jung Myung-suk.

JMS members from a cultural centre came to her school and gained the attention of students by offering free dance and guitar lessons. Years later, she discovered the cultural centre was built by JMS, deliberately located near her school to recruit students.

“My main concern was to lose weight,” says Kim, now in her mid-30s. “All my friends would spend their time doing fun things, but I spent all my time within the group and with its members. In college, my grades suffered because of this, and I even ran away from home for the first time when my mother found out about my involvement.”

After four years of living a double life that forced her to continuously lie to her parents and friends about her daily activities, she eventually came upon the website that JMS members had told her to never visit. It was a site full of testimonies from past JMS members exposing the group’s web of secrets and lies.

I spent all my time within the group and with its members ... I even ran away from home for the first time

“Our pastor Jung Myung-suk was hiding in Hong Kong and my friends in the group would send him pictures of themselves in bikinis,” she says. “Just as I was beginning to think something was fishy, Jung was captured by Chinese officials and sent back to South Korea.”

In 2009, Jung was sentenced to 10 years’ prison for sexual assault and harassment, having told followers they would be “saved” if they had sex with him.

Despite such incidents and the work carried out by the likes of Pastor Jo, condemnation of these groups is by no means unanimous. Sung Hae-young, a professor of Religious Studies at Seoul National University, is one academic willing to offer a defence of their right to believe, preach and proselytise as they choose.

What is the appeal?

For all his criticism of these fringe groups, Pastor Jo concedes their appeal reveals a grim truth about South Korean society, and the way the groups address a search for meaning not found elsewhere. He notes that about 70 per cent of South Koreans in fringe churches were previously members of more traditional congregations.

“We cannot deny that these groups offer a community and a sense of belonging at a time when our country has the highest suicide rate among OECD countries and people are addicted to work or studying,” he says.

Jo also notes the parallels in the psychology of people who join these fringe groups with the pathologies of addiction.

“They have similar mental states as those addicted to drugs and gambling,” he says. “In all these issues dealing with addiction, experts agree that the most important healing factor is to find a community.

“Does our current society and our churches have the ability to create and foster this type of community for people in need? This might be a big reason people are heading towards these fringe churches.

“It’s important to note that members in these groups face persecution together from society, churches, their family and friends. So it’s inevitable that their bonds get stronger the more they are attacked from outside.”

All these cult leaders know deep inside that they are swindlers

Kim, the former JMS member, recalls being lured into the group at a time when she felt particularly vulnerable. Indeed, high school life can be intensely competitive and pressurised for South Korean teenagers as they vie for coveted university positions.

“I felt like members of the group were my life comrades, and they made me happier than when I was at home,” she says. “Everyone was so kind to me, and we would do almost everything together, whether it was preparing for a theater production or taking a trip to the beach.”

Ahn So-young recalls being drawn to Shincheonji after she discovered her married pastor had inappropriate relationships with female worshippers. She has since enrolled in a Christian seminary and counsels other young people who are struggling with similar experiences with pseudo-religious groups. The experience has made her increasingly clear-eyed about the objectives of these groups.

“Money and fame,” she says. “All these cult leaders know deep inside that they are swindlers.”